Real-Time Task Reservations and Scheduling in Linux

Baby's first steps into kernel development

Cameron Lee, 12/21/2025 - 11:18pm

Preface

One of the most challenging and interesting classes I've taken at SDSU

is

Dr. Hyunjong Choi's Theory

Of Real-Time Systems course. As part of this class, I modified the

Linux kernel to support explicit real-time task reservations, periodic

execution, and end-to-end latency monitoring. While Linux supports

several real-time scheduling mechanisms, implementing textbook

real-time scheduling models required working directly with core kernel

structures like the

task_struct,

scheduler, and kernel timers. Using custom kernel system calls, I

implemented Rate Monotonic scheduling and partitioned Earliest

Deadline First scheduling across multiple CPU cores. This post focuses

less on scheduling theory and more on what building these features

revealed about how the Linux kernel represents tasks and enforces

behavior across context switches.

Background

This project uses classic real-time models, with tasks that are

periodic and declare a computation budget

C

and a period

T

. Schedulability depends on whether the kernel can allocate CPU time

to all tasks without violating these constraints.

Enforcing this model in Linux required more than just choosing a

scheduling policy. It required tracking execution time across context

switches, associating timing state with each task, and integrating

kernel timers into the task lifecycle. These requirements pushed the

project into core kernel structures and scheduler hot paths, which

became the primary learning focus for me.

For development of this project I modified and compiled the Raspberry

Pi Kernel-4.9.80

CanaKit Raspberry Pi 3

The first thing I had to figure out was how to track all my new

information, like the budget and period. It needed to be something

that was intrinsically tied with the tasks themselves and would

persist between different states and changes. This eventually led me

to the monster that is the

task_struct. When I got to this point of

researching how this was put together I was WOW'd by how massive the

file was, I didn't even know structs could be that big. If you've ever

worked with anything relating to threads/processes in the Linux kernel

you know exactly what I'm talking about, it's basically unavoidable.

For those who don't know, a quick tl;dr: the

task_struct is a gigantic struct with 300+

different fields (depending on the kernel version), with many of those

being other structs with more fields! The

task_struct is the DNA of every process in

Linux and has every single piece of information you'd want to know

about said process. There's a few different ways to access this

magical structure, for this project I used

find_task_by_pid_ns()

and

task_active_pid_ns()

in order to get the struct using the task's pid and namespace.

Crossing The Boundary Between User and Kernel

One of the coolest parts of the project was adding custom system calls

and realizing how different kernel code feels. At first I thought that

making system calls would be like making a normal function, but in

practice you have to be programming with extreme caution every step of

the way. The kernel has to treat everything with suspicion, arguments

from the userspace can't be trusted and there are no error cases that

can be ignored because continuing with a partially validated state

risks corrupting global kernel data.

Even the mechanics of adding the system call was a headache. In order

to add new system calls, you have to specify in

unistd.h

how many entries you need to have in your system call table. I lost

more time than I'd like to admit toiling over this one line:

#define __NR_syscalls (401) not realizing

that the table had to be aligned in increments of four...

Defining the system call itself was also very different, you have to

use the

SYSCALL_DEFINE*

macro, with the asterisk replaced with however many parameters you

need. At one point, I needed to pass seven parameters in order to

support chain metadata, only to discover that

SYSCALL_DEFINE6 was the hard limit. The

solution was to pack all the information as my own

chain_struct and pass it as a

void *. In the user space things like this

would proabably just feel like an inconvenience, but in the kernel, it

felt purposeful and made me design with more intention and with

efficiency in mind.

During development, I leaned on kernel modules to make testing a

little easier. I created the system calls with hooks that could be

modified with loadable modules. Being able to test functionality

without needing to rebuild the entire kernel saved me time and some

sanity, but the process was still slow compared to user-space work. I

really got a feel for how expensive minor mistakes become at this

level.

Context Switches and Time Accounting

Most of the work for this part of the project resides in

kernel/sched/core.c

yet another intimidating file, this is where the Linux scheduler's

core logic is written. This file decides when a task stops running,

when another one begins, and everything in between.

At the center of this, is the

__schedule(). This function is evoked

every time we need a context switch, whether it was because the

current task was preempted, blocked, or voluntarily gave up execution.

Inside

__schedule(), the scheduler picks

the next task to run, does some bookkeeping, and triggers the context

switch.

This made for the ideal place for time tracking. When a

new task is scheduled in, the kernel has a precise moment where CPU

ownership changes. By recording timestamps at the point when a new

task is scheduled and when said task completes, execution time can be

found as the difference between these two events.

One minor detail made this a little more complicated than it seems: a

task doesn't necessarily run in one continuous stretch. A task could

be preempted, rescheduled, blocked by I/O, etc. Each of these events

gives a separate "slice" of the execution time. Because of this,

execution time can't be measured with one start and end timestamp.

Instead, we have to make use of a per-task time accumulator, where

every time a task is scheduled out, the elapsed time since it was last

scheduled in is added. The accumulator is then reset at the beginning

of the next period.

Implementing the accumulator forced me to be precise about

where each piece of information lived and when it was updated. This

was one of the kernel's hottest paths, and as such the tiniest changes

could propogate through the entire system.

Subtle foreshadowing

The Bug That Bricked My Raspberry Pi

This leads me to the last night that I had to finish the project.

Right when I started to think I had a grasp on this whole kernel

development business. I was implementing the logic for measuring

end-to-end latency for chained tasks and it was finally time to test

my code. I ran the cross compiler, had to go back to fix some minor

mistakes, and booted up the Pi.

Although this time, I wasn't getting any response from my serial

connection. I thought maybe the kernel got corrupted, so I clean built

it again but got the same result. I was beginning to panic. This had

never happened before. I had compiled this kernel hundreds of times at

this point and I had never seen this before. Usually if I have some

kind of error in my code the compiler would break and I could go back

to fix it, but this time I wasn't getting any errors or warnings.

My next thought was that maybe the hardware had given up on me. I

tried multiple different ports and cables, I even borrowed another

group's RPI kit and tried to run my kernel on all of their hardware

and nothing changed. Maybe the problem was somehow with the serial

connection to my laptop? I tore the lab apart trying to find an hdmi

cable, keyboard, and mouse so I could run the Pi independently and

when I booted up, I was greeted with this wonderful screen:

I would later learn this is the splash screen from the GPU when the

kernel can't boot.

what.

After hours of debugging, reflashing, and second-guessing the

hardware, the process started feeling less like engineering and more

like faith. Recompile. Reboot. Wait. Stare. Hope. Emotionally, the

night felt like I was in Las Vegas hoping that one more pull of the

slot machine would finally pay out. Same ritual, different casino.

Recompiling the kernel at 4am feels statistically indistinguishable

from gambling

Eventually, I found my error and I felt like the biggest idiot in the

world. See, in my

__schedule() (what'd I

call it? One of the hottest paths in the linux kernel?), I had

implemented logic for tracking chain information in a shared

chain_struct that I added a pointer for in

the

task_struct. But somehow, I failed to

think about the fact that this code was running for

every

instance of

every

process

EVERY

time it ran, and I was

NOT

implementing chain information for every process on the machine.

Without checking for the

chain_struct first, I was dereferencing a

null pointer like a bajillion times a second. So bad was this mistake

that the kernel couldn't even boot to a point where I could see any

errors. *sigh* You live and you learn.

Debugging in the Kernel Is a Different Beast

And that is no exaggeration. Slow compile times, long reboot cycles,

limited feedback; so many factors play into needing to get things

right the first time. There is no carelessness that will go unpunished

in the kernel, and the benefit of understanding the system and

planning ahead is priceless. A whole host of unique challenges are

introduced as well.

Early on, every kernel change meant manually copying the

configuration, mounting the target filesystem, backing up the kernel

image, cross-compiling, loading modules, and unmounting everything

again. It worked, but each iteration added friction, and debugging

became as much about patience as correctness.

Eventually, I realized the real problem wasn't in the kernel code

itself, but the minor inefficiencies at every turn. I scripted the

entire process into a single command, turning minutes of repetitive

monotony into one line. That small change dramatically reduced the

overhead of each iteration and made it easier to focus more on writing

the code and less on running the code.

How This Changed My Work

I learned a (pardon my french) sh*t ton in this project, I would say

this project is at least top 3 impact to my development as a

programmer. I had to learn how to be more deliberate with my

structure; Think about cleanup paths early, asking questions like "if

this fails halfway what state am I leaving behind?"; Make sure I'm

maintaining everything properly: canceling timers, freeing memory,

resetting fields, etc; Writing code that future me will be able to

debug, like making sure to include verbose and detailed printouts as I

go, rather than going back and adding print statements everywhere

after it breaks (I found myself recompiling the kernel multiple times

just because I needed to make my printouts more readable for myself).

The kernel has no safety net, and learning to work without one

reshaped how I write code everywhere else. I'm much more deliberate,

cautious, and better at breaking down large complex problems. These

habits spread across all domains, and they're something I'll carry

forward for the rest of my career.

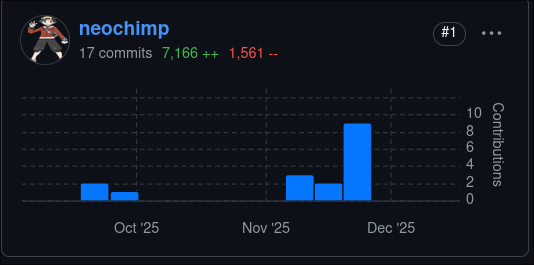

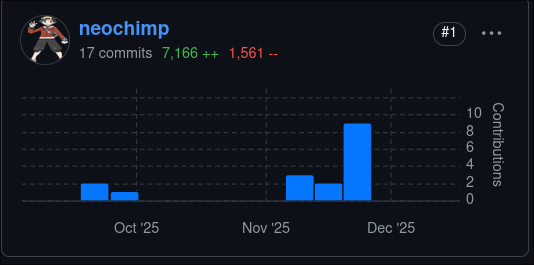

7,166 lines of code later...